The Shingle Style, as it has come to be known, was originally a relatively short-lived offshoot of the Victorian Queen Anne Revival style during the late 19th century in the United States. This style has, over the last century, come to epitomize the leisure and graciousness of New England resort communities from Mt. Desert, Maine to Nantucket, Massachusetts to the coastal communities of Rhode Island to the Hamptons of Long Island, New York. The noted Yale architectural historian Vincent Scully aptly called it “the architecture of the American summer.”

Isaac Bell House

Although there is no definitive start or end date to its first flowering, many architectural historians would point to the construction of the Newport Casino in Newport, RI in 1880 as marking its beginning. The building was the first project commission for the newly formed partnership of Charles Follen McKim, William Rutherford Mead, and Stanford White. It was also the first example of a new project type dedicated to leisure and sport: the country club. This project would help launch the firm into a level of prominence and productivity that would have an enormous effect on the architecture of America. It was designed in a style that was derived from the Queen Anne Revival style, which was popular at the time, but with a level of inventiveness and creativity that marked the passage into a new style. Vincent Scully would eventually name this new design approach “The Shingle Style,” in his seminal text of the same name.

Tilton House

Marked by an almost painterly use of shingles cut in different decorative styles, the building had both a respect for previous styles but also a freshness and a lightness that was not characteristic of the Queen Anne Revival period, which often had polychromy and heavy exposed timbering on the exterior. The style is characterized by the same sweeping, surrounding porches and asymmetric arrangement that was typical of the Queen Anne Revival Style. From the Colonial Revival style it adopted classical details, gambrel roofs and shed dormers. From the Richardsonian Style, it adopted heavy rustic foundations and Romanesque aches. Together these seemingly disparate elements all came together harmoniously.

But by about 1900, the Shingle Style was no longer the preferred style of mansions being built in Newport or other fashionable resort communities. As early as 1888, architects like Richard Morris Hunt were designing highly derivative and formal palaces like Marble House and the Breakers, as the Gilded Age barons competed to outdo one another in the grandeur and expense of the homes they were building for their families in summer resort communities. In 1900, the very firm that probably launched the Shingle Style was designing white, formal mansions like Rosecliff, which was the complete antithesis of the rustic and relaxed Shingle Style. However, elsewhere the Shingle Style continued to grow and spread. Pictures of the Newport Casino and Isaac Bell House were published in national architectural magazines where architects around the country (like Frank Lloyd Wright and many others) took note and emulated the style in their own work.

Lawson House

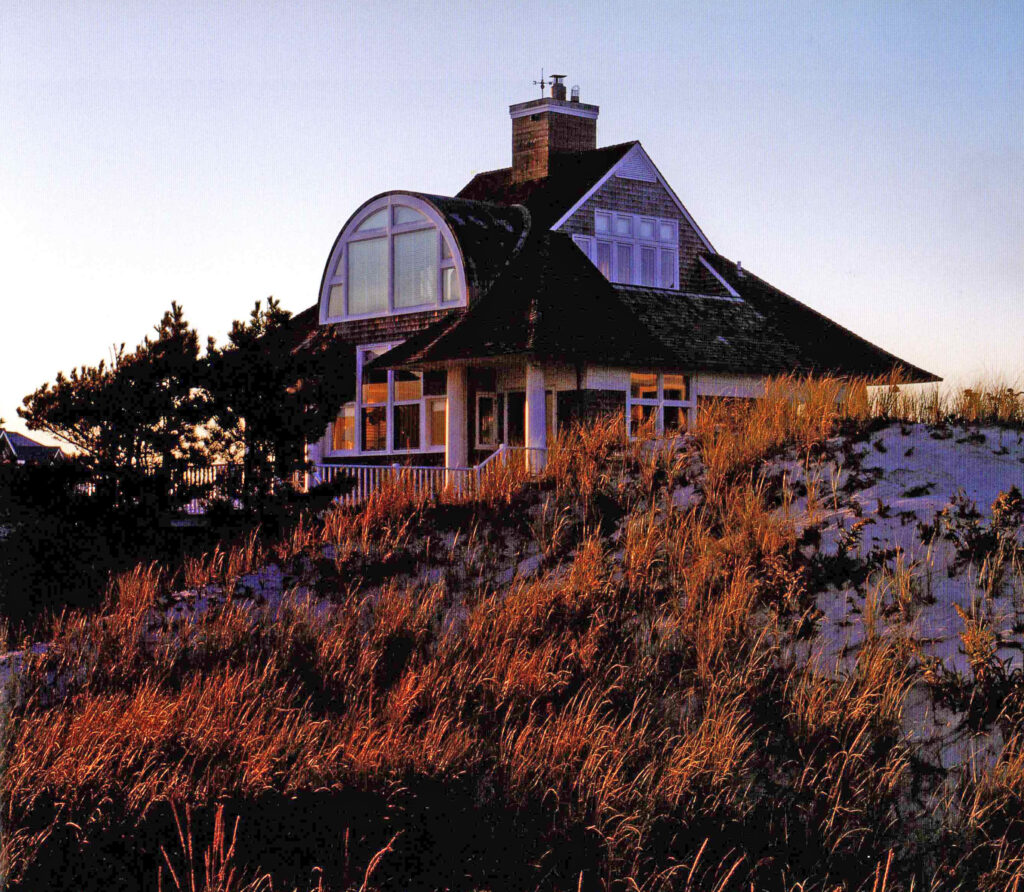

Because of the practicality the Shingle Style and the abundance of cedar on the North American continent, it never faded from the scene completely. After Vincent Scully’s book The Shingle Style in 1945 and its subsequent republishing in 1955, 1971, and 1974, the style regained stature in academic circles. Young architects trained at Yale, including Robert A.M. Stern and Jaquelin Robertson, saw the possibility of taking characteristics of the style and applying them to seminal works like the Lawson House (Stern, 1979-81, Quogue) and the Flinn Residence (Robertson, 1978-79, East Hampton). These buildings, once published, helped breathe new life into the style a century after it was first invented. Since then, the style has continued to grow and flourish as it hits the perfect balance between formal and casual, and between traditional and modern, for many owners’ visions of a summer cottage or weekend retreat.

Flinn House

Why has this style outlived and out-performed all the many revival styles like Colonial Revival, Greek Revival, Gothic Revival, and so many other formal architectural styles? First, the style is, by its nature, asymmetrical and free flowing in plan. It, therefore, is easily adaptable to complex programs and can focus the building on views and topographic conditions that are unique to each project.

The exterior of shingle style is, almost by definition, naturally red or yellow cedar shingles artistically arranged in patterns. These, if properly installed, can last 40-50 years without being painted or stained, and age to a beautiful brown or silver patina, depending. There is something elegant about this and appropriate to a resort home, where the focus is on enjoyment and less on spending weekends painting and refinishing exterior walls.

Thirdly, it is perhaps because the Shingle Style is associated with the early Gilded Era mansions of Newport and other grand communities of that time, which promised prosperity and leisure. These summer houses were built at a time of rapid economic growth in the United States and therefore visually extended the promise of gracious living to a widening section of society. They were big enough to be comfortable, but not so large as to be unmanageable, as many of the palatial Gilded Age buildings in Newport became in the period after World War I and the Great Depression. They have held up well and so they became the Grande Dames of the communities in which they were built. They have the patina of age and respectability, but maintained the solidity of strength.

Today, it has become the de facto style of resort communities throughout the United States, but most specifically in New England. Now the number of Shingle Style homes around the country is in the tens of thousands, and yet the charm of them has not diminished in that they vary widely by location, architect, and project. The style succeeds because it has no heavy stylistic rules. In the early work at the Newport Casino and elsewhere in Rhode Island, the architects of the Gilded Age gave us a set of architectural forms and tools that work remarkably well to this very day and hopefully far into the future!

Cliff Walk House, remodeled by A4 Architecture

Looking to remodel your home? Let’s connect.

Join the Architectural Forum to stay up-to-date with architectural news from Rhode Island and abroad.

Ross Sinclair Cann, AIA, LEED AP, is an author, historian, educator, and practicing architect at A4 Architecture and lives and works in Newport, Rhode Island. He studied with Professor Scully as an undergraduate at Yale and was a teaching assistant for Robert A.M. Stern at the Columbia School of Architecture in New York. He has worked on dozens of buildings by McKim Mead and White, Peabody and Sterns, and other noted architects of the Gilded Age, and has frequently designed renovations and new buildings in the Shingle Style.

This article has been featured in the May 2021 edition of The 401, Rhode Island’s Luxury Real Estate magazine.

“Together these seemly disparate elements all came together harmoniously.”

You mean “seemingly”.

Nice article. I thought the Low house in Bristol was the first shingle style but looks like they followed the casino

I’ve built two of Bob Sterns shingle style designs and developed a 100 lot shingle style community San Juan Passage in Anacortes, Washington (Facebook) which was well received