Of all the many prolific and nationally recognized architects to work in Newport, Rhode Island, none have been more nationally recognized or more prolific with their designs than the firm of McKim, Mead & White.

This firm was founded in New York originally as McKim, Mead & Bigelow in 1878, but William Bigelow split from the firm when his sister abandoned Charles McKim in 1879, and was replaced by the young designer Stanford White. It was at this point that the fortunes of the firm began to rise meteorically.

Charles Follen McKim (1847-1909) was famous early in his career for being the third American to be educated in Architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He returned to the United States and apprenticed for two years with the office of Henry Hobson Richardson at 57 Broadway before setting up his own practice down the hall. When he left in 1872 to setup in his own office, he was immediately replaced by a young, talented 19 year-old artist named Stanford White who he would recruit in 1879 to join his office.

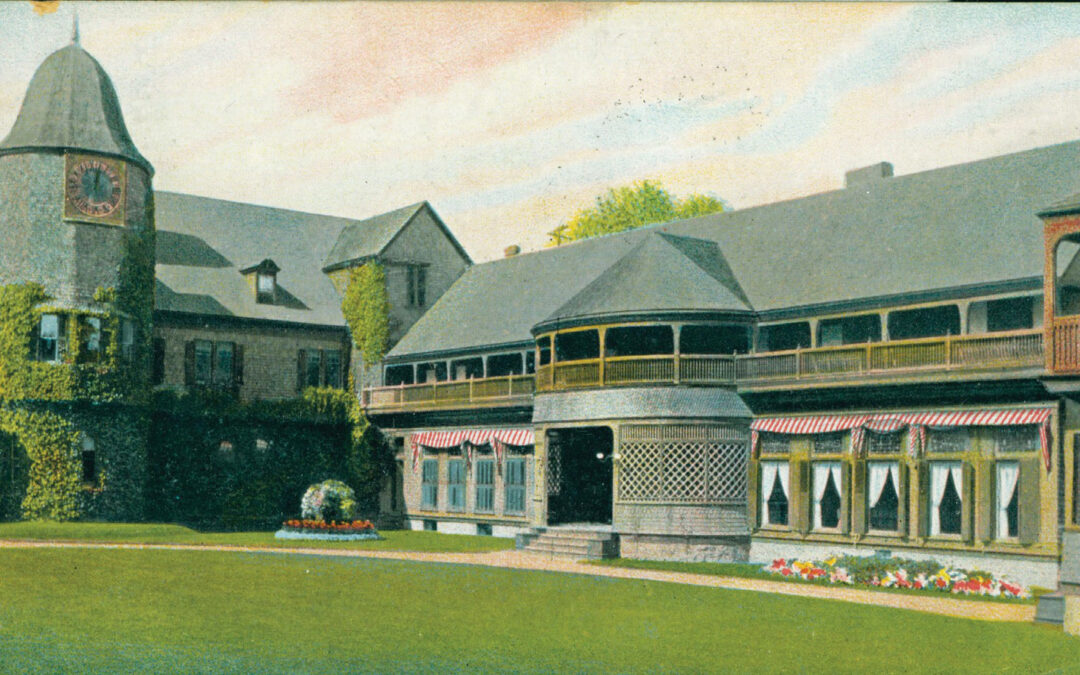

McKim, Mead & White’s first project as a firm was the Newport Casino for James Gordon Bennett. This project was designed in what Yale architectural scholar Vincent Scully later coined the “Shingle Style.” This style was so named because cedar shingles were used in a variety of patterns in an almost painterly way around the exterior of the building. It was an offshoot and evolution from the Queen Anne Revival Style which was widely employed during the mid-Victorian era but was decidedly less busy in its use of timbering and much less polychromic than the earlier style.

The Shingle Style, although relatively short lived during the Gilded Age, would have a lasting and profound impact upon the American Architectural character and remains one of the most widely employed design styles in New England resort communities to this day. In fact, architect and historian Robert A.M. Stern credits McKim, Mead & White as the most influential American architects in history with the exception of Frank Lloyd Wright.

In addition to the Newport Casino, McKim, Mead & White produced numerous Shingle Style houses in Newport early in their careers including the Samuel Tilton House (1881), the Isaac Bell House (1882), and the Samuel Coleman House (1883), among others. Each of these are considered small gems in the grand treasury of the work as a firm, which would include stately civic buildings, clubs, and other grand structures throughout the United States, including the Rhode Island State House, the Boston Public Library, among many other large and notable buildings.

As McKim, Mead & White’s fame rose, so did the size and budgets of their projects. Soon the charming and original Shingle Style was not sufficient for the grand visions and expectations of their clients. Of the thirteen projects they are credited with having designed as a firm in Newport, the last one that they designed for the silver heiress Tessie Oelrichs, was completed in 1901. This house, known as Rosecliff after the cottage that previously sat on the site, is a grand white terracotta palace. Built on a H-shaped plan with an enormous ballroom in the middle, this “Newport summer cottage” was designed to allow the owners to entertain the other summer colonists in high style. While beautiful and grand in the extreme, the design was largely derivative of European palace models and lacked the originality and artistic freedom and creativity demonstrated in the firm’s far smaller Shingle Style buildings.

The spectacular rise of McKim, Mead & White came to an even more spectacular end when a 37 year old millionaire named Harry Kendall Thaw shot Stanford White three times on the rooftop terrace of Madison Square Garden, the most opulent of New York clubs at the time and one of White’s own designs. The shooting was over a spat involving Evelyn Nesbit, Thaw’s wife and was called the “crime of the century.” It was front page news for a long time afterword, becoming fodder for books like E.L. Doctorow’s “Ragtime” and the movie made from that work.

At the time of White’s death, the firm had become the largest in the country, if not the world, with more than 100 employees. While the firm of McKim, Mead & White continued to design great works throughout the country, the loss of Stanford White’s creative genius and oversized personality mean that the firm’s best days were behind them.

The country was changing as well. While the institution of income tax began in 1862, it was only a 2% fee on incomes equivalent today of over $120,000, meaning that only about 10% paid any tax at all. In 1913, with the passage of the 13th amendment, the passage of a permanent progressive tax was put in place. With the debts of World War I to be paid for the rate of tax on one million dollars of income increased from 7% in 1913 to 73% in 1921. The advent of the Great Depression in 1929 was the final blow to the extraordinary buildings that arose during America’s “Gilded Age.” And yet the buildings of that period continue to exist as a reminder of a time of opulence shaped by talented architects like McKim, Mead & White.

Ross Sinclair Cann, AIA is an historian, educator and practicing architect living and working in Newport for A4 Architecture He holds architectural degrees from Yale, Cambridge and Columbia Universities and is a member of a numerous committees, commissions, and boards.