In the realm of architecture change is inevitable. It can come in the form of disintegration or renovation. Buildings are made of imperfect materials and are subjected to rain, snow, heat, and cold. Similarly, as civilization evolves, buildings need to evolve along with them. Since Colonial Era plumbing, electricity and issues of sustainability have all needed to be added to buildings. While we love our Colonial buildings, I do not believe anyone misses the “privies” that once were universal or cooking in a pot over the fire in the fireplace.

The trick and challenge is to take the best of the old and marry it to the best of the present to make the building work for the future.

There are many who confuse Historic Districts with simply fighting any change at all. This prevents building owners from making their homes and structures from working for them thereby preventing renovations and encouraging those owners to seek other locations or communities.

The people who volunteer to serve on Historic District Commissions tend to be strong willed and dedicated to their own vision of what preservation means. They are not compensated for the long hours and hard work that these positions require. But as a result, the boards can become unbalanced, with all the focus being dedicated to preventing change rather than helping guide change in the most positive direction.

There is a movement afoot to broaden the perspective of what preservation means to direct focus on the people and the meaning of what is preserved rather than simply thinking of the buildings as unchangeable structures. For instance, funding the maintenance of the fine homes of Confederate generals over the preservation of slave shacks is one example of how the support of high architecture has trumped the broader lessons and history that might have been spotlighted.

The fact of the matter is that maintaining balance is hard. It is much easier to fight any change at all or conversely, for developers, declare that all change is good. Neither of these approaches works in the long term. Prevention of change leads to a long, slow decay of the buildings that cannot be modified to meet new needs and wholesale destruction of the old prevents the kind of continuity that fosters community cohesion and solidity.

It is important to remember that every old and beloved structure once replaced what was there before. In Newport, oftentimes a grand house replaced another worthy structure. For instance, John Russell Pope’s beloved Waves replaced the elaborate and grand Lippitt’s castle. The current Kingscote came about from the splitting of the previous George Noble Jones house and creating an addition by McKim, Mead, and White in the middle, which changed the structure dramatically while still honoring the original design. The Elms replaced three commodious cottages which once sat on the current site. In each case the current much beloved building would likely have been prevented by an iron-fisted Historic District Commission intent on preventing change from occurring.

As a professional architect, I would love to see the commissions and boards give some flexibility to those who are engaged by owners to try to solve their functional challenges while adhering to zoning ordinances, building codes, the challenges of sustainability, and the limitations of budget. It was the openness of clients and societies in the past that allowed all the beloved buildings and structures that exist today to be created in the first place.

So, if balance is required, how is this balance to be proscribed and maintained? The Newport Historic District ordinance already does this to a large degree. The very preamble to this Historic District ordinance declares “The Purpose of the Historic District Zoning in the City of Newport is to protect historic assets and to guide new growth in ways that enrich and maintain Newport’s sense of place and historic character, for now and future generations.” This implies a balance between maintaining the best of the past while enabling the change and growth that is necessary for the future. This is confirmed by 17.80.010.2: “Stabilize and improve property values within the districts” 17.80.010.4: “Strengthen the local economy” and 17.80.010.5 “Promote the use of the historic district for the education, pleasure, and welfare of the citizens of the city of Newport.” All of these directives seem to promote the compatible improvement of properties by their owners within the district to make them more functional, beautiful, and valuable. These sections of the code are promises and guarantees to the owners of the properties within the district that they will not be denied their rights to maintain and improve their properties as any owner would naturally want to.

The properties within the Historic District are divided into two main categories: contributing and non-contributing. “Contributing” properties are those that are built within a given district’s period of significance and character whereas “non-contributing” properties are deemed to not meet that qualification.

For contributing properties here is an abbreviation of the standards for treatment;

- Retain historic character;

- Avoid conjecture;

- Maintain significant alterations;

- Preserve character;

- Repair before replacement;

- Avoid damaging treatments;

- Minimize farm from alterations

“Significant” features are generally those “character defining” elements which give the building its form and design quality. The large door opening for instance is a character defining feature of a carriage house whereas a piece of garden ornament would not be.

If buildings are to continue to maintain their vital role they must function within the modern world for their owners or the promise of value and community growth are denied, conversely, the buildings within historic districts owe their neighbors the compatibility and continuity that they continue to be part of the authentic architectural fabric which is Newport. It falls to the owners, their architects and the various commissions to help steer projects between the two poles of too little change and too much.

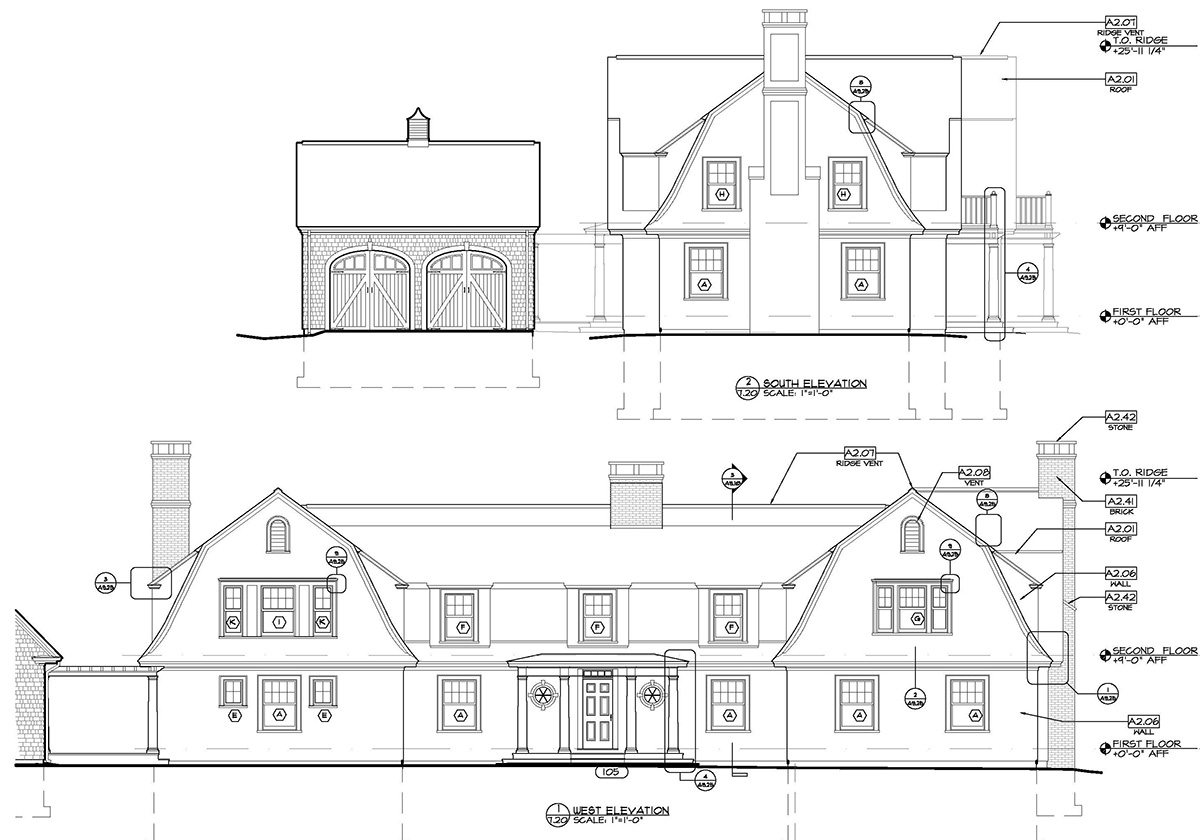

The pictures and drawings are within the Newport Historic District of the renovation of a 1950s house into a “Newport Shingle Style Cottage”

Ross Cann, RA, AIA, LEED AP, is an author, historian, and practicing architect living and working in Newport, RI. He holds degrees in Architecture and Architectural History from Yale, Cambridge, and Columbia Universities.