In a recent blog about the evolution of “The Ideal Architect” over time, it’s not just real architects who play a role, but fictional ones as well. Howard Roark, the protagonist of Ayn Rand’s 1943 novel The Fountainhead, stands as a towering figure in literary history—an architect who, despite never breaking ground on a single real-world structure, has left an indelible mark on culture and philosophy. Roark, perhaps “the most famous architect who never lived,” is the embodiment of Rand’s Objectivist philosophy, a testament to uncompromising individualism and the unwavering pursuit of personal vision.

Born from Rand’s desire to create an “ideal man,” Roark is portrayed as an architect of immense creative talent and integrity, who refuses to bend to the whims of a society that champions mediocrity and collectivism. His philosophy is simple and absolute: a building’s design must be true to its purpose and materials, and the creator’s vision is paramount. This unwavering stance pits him against the architectural establishment, personified by the sycophantic architect Peter Keating and the manipulative architectural critic Ellsworth Toohey. For Roark, the struggle is not merely about aesthetics but about the sanctity of the individual and the right to create for one’s own sake.

Roark is presented as an ideal man who embodies Ayn Rand’s Objectivist philosophy, which values reason, individualism, and the pursuit of one’s own happiness. His unwavering integrity and focus on his own creative vision exemplify these ideals.

The cultural impact of The Fountainhead over time has been as monumental and polarizing as Roark’s fictional buildings in the novel. It has been a touchstone for artists and architects, inspiring generations to prioritize design integrity and modernist principles. Beyond the artistic realm, Roark became an icon for Libertarians and Conservatives, his relentless individualism resonating with those who champion free markets and limited government. His character has been both lauded as a heroic ideal and condemned as a symbol of callous selfishness, a debate that continues to fuel discussions about the role of the individual in society.

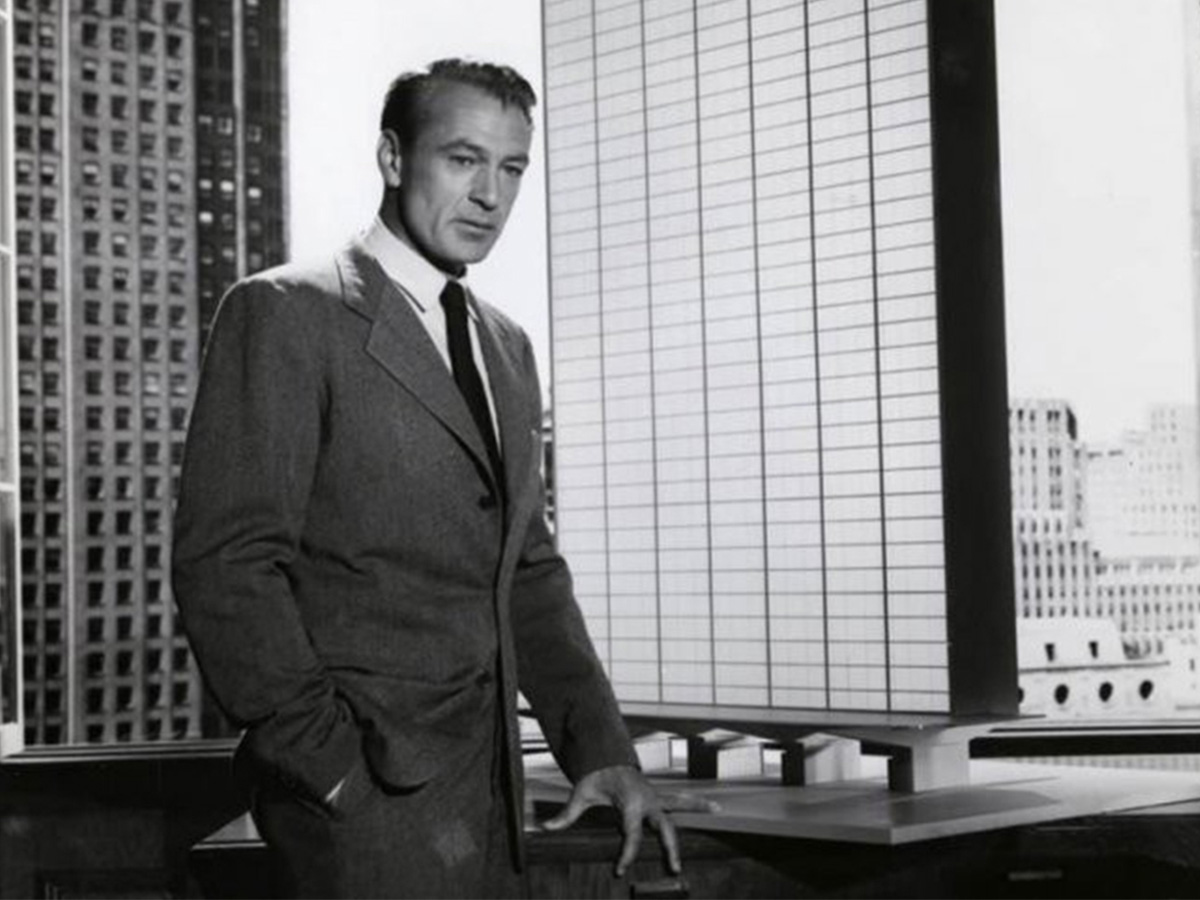

The novel’s controversial nature was amplified by its 1949 film adaptation, a stark and visually dramatic production starring Gary Cooper as Roark and Patricia Neal as his equally fiercely independent lover, Dominique Francon. With a screenplay penned by Rand herself, the film is a faithful (although somewhat melodramatic) distillation of the novel’s philosophical core.

Cooper’s portrayal of Roark captured the architect’s stoic determination, though many critics found his performance stiff and lacking the intellectual fire that burned within the novel’s character. Neal, in a role that mirrored her own tumultuous off-screen affair with the married Cooper, brought a fiery intensity to Dominique. The film’s stark black-and-white cinematography and dramatic (at times clumsily phallic) architectural imagery created a visually arresting, if unsubtle, cinematic experience—particularly for 1949.

Roark is fiercely independent and unwilling to compromise his artistic vision or beliefs, even when facing societal pressure.

Upon its release, the movie was largely panned by critics, who dismissed it as “wordy, involved, and pretentious.” However, like the novel, the film has cultivated a legacy, appreciated by some for its bold visual style and unapologetic embrace of Rand’s philosophy. For many, the film with its impassioned speeches and dramatic confrontations remains a potent, if controversial, cinematic exploration of individualism versus collectivism, forever cementing Howard Roark’s place as a cultural lightning rod.

I read all 680 pages of a paperback copy of The Fountainhead in a single (very long) sitting as a young architectural student in 1985. I was, of course, entranced by the idea of an architect as a creative genius bending the world to his will and overcoming all the obstacles of mediocrity and budget placed in his way. Now, 40 years later, I am much more aware that architecture is a collective art and never a purely creative or artistic pursuit. It must address client needs, budget, building and zoning codes, constructability, its impact on surrounding buildings, and a dozen other external inputs. These are details that are glossed over in a novel written by a non-architect.

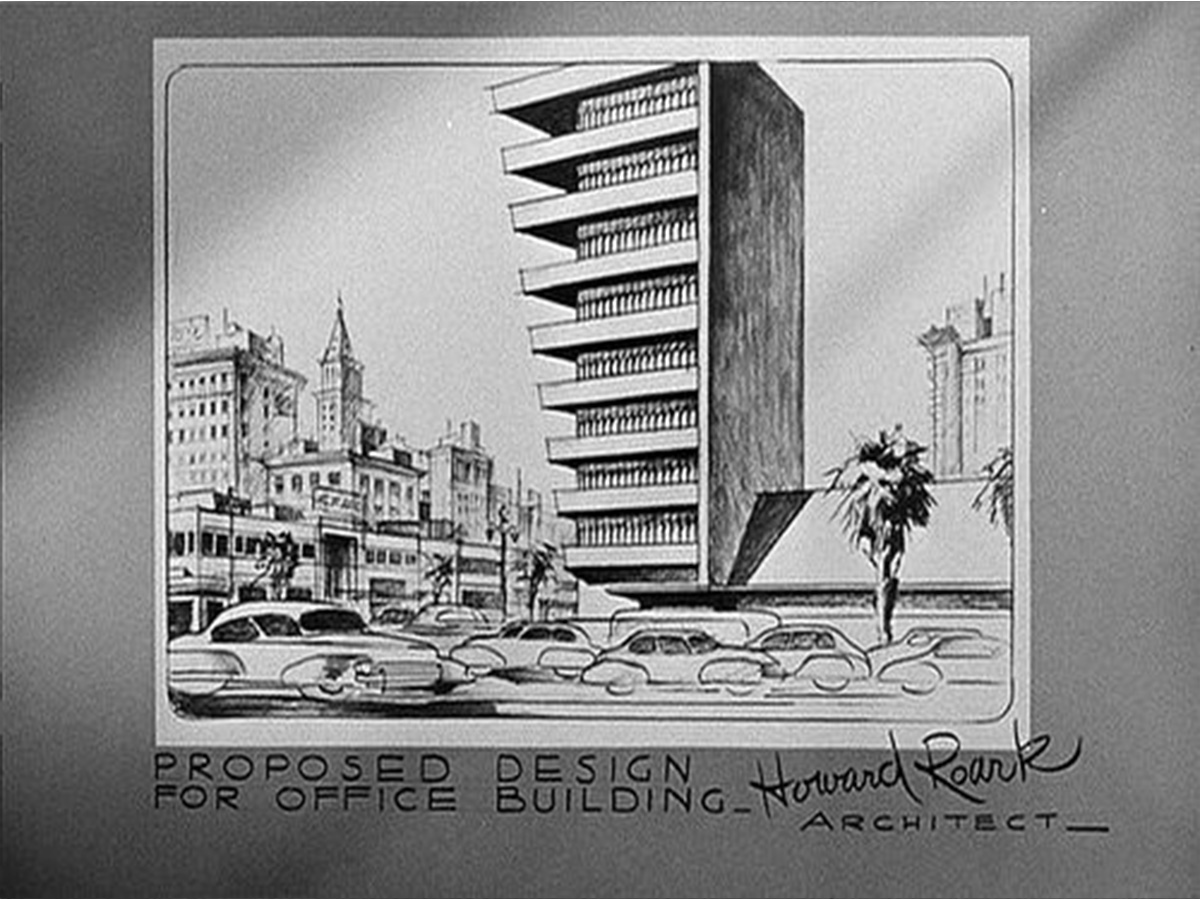

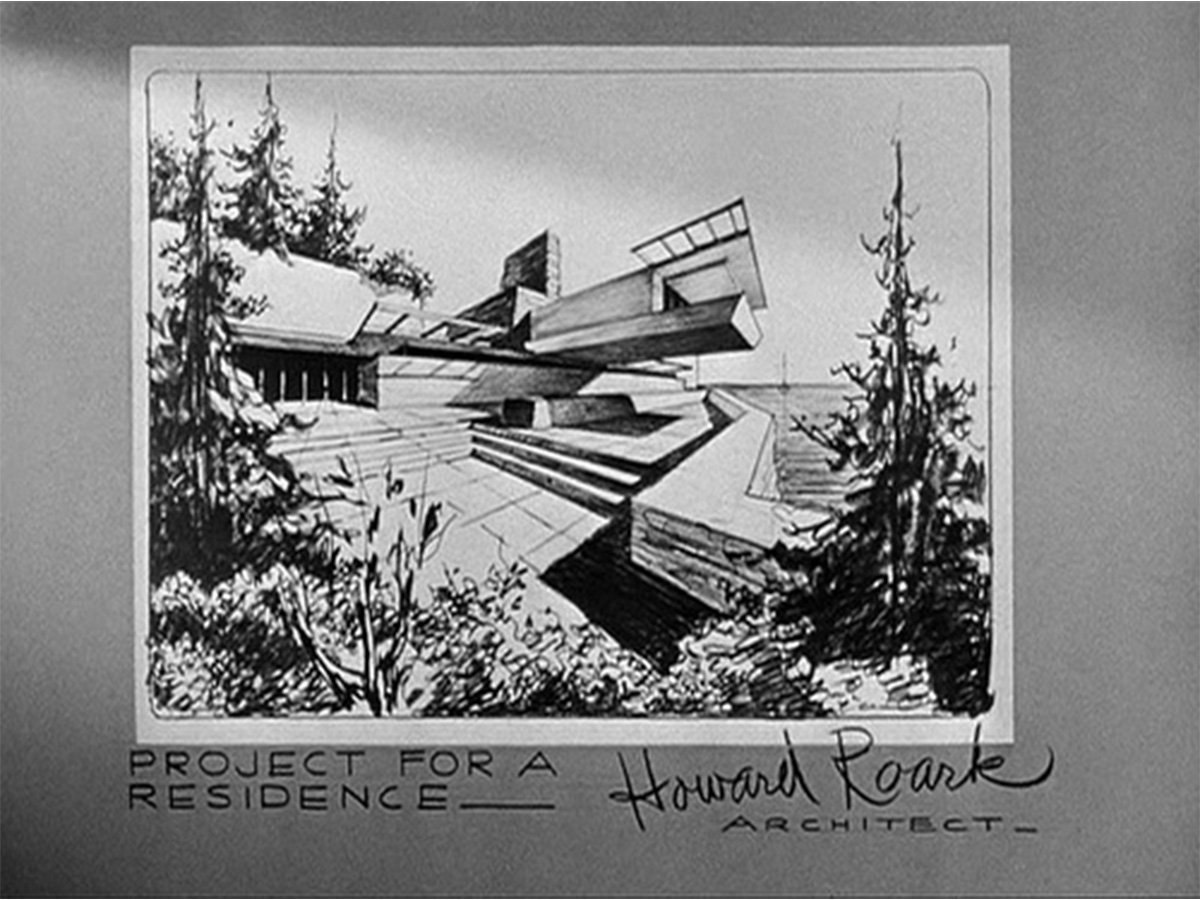

The character of Howard Roark seems largely drawn from an idealized version of Frank Lloyd Wright’s career. He too was a man who created as much controversy as he did great buildings over his long lifetime which is evident in some of the designs depicted in the novel and movie.

Roark challenges traditional architectural styles and practices, preferring to create buildings that are functional and aesthetically unique.

Roark also helped create in the public imagination an image of “The Architect” as a self-centered genius who cared little for the opinions of others. This perception has been an obstacle to the profession for more than sixty years and has often deterred people from engaging architects for fear they would ride roughshod over their ideas and concerns, an unfounded concern, in my experience.

Another thing that catches the eye of an architect who has been practicing for 40 years is that Roark somehow designs all his buildings by himself, alone at a drafting board at night. Buildings are extraordinarily complex undertakings that require the collaboration of many people to plan and detail. Architecture is the ultimate team sport. Today, architects strive to find a balance between producing inventive designs and meeting the more pragmatic needs of a project. In most instances, they help create wonderful buildings that serve both their owners and broader society well.

If you would like to partner with A4 Architecture to help create a beautiful home or building in the New England region, please reach out to us. We look forward to learning more about the project you are hoping to build.

Ross Sinclair Cann, AIA, LEED AP, is a historian, educator, author, and practicing architect living and working in Newport for A4 Architecture and is Founding Chairman of the Newport Architectural Forum. He holds honor degrees in Architecture and Architectural History from Yale, Cambridge, and Columbia Universities, teaches in the Circle of Scholars program at Salve Regina, and has been a licensed architect since 1992.