Newport is famous for many things and for many “firsts” as it was the fifth largest city in colonial America and a major and prosperous settlement before the Revolutionary War. Among the things that Newport takes great pride in for is being a place of tremendous religious freedom at a time in history when that was a very rare condition.

The area around Queen Anne Square, as Washington Square was known as until the death of the first president, was surrounded by the houses of worship of many faiths, including the Quaker, Baptist, Anglican, and Jewish faiths. In fact, the Touro Synagogue was located directly across the street from the freshwater spring that originally gave life to the community and served as its origin point in the founding documents of 1639.

Although not the first synagogue in the American Colonies, Newport’s Touro Synagogue has long been the oldest remaining synagogue in the country. It serves as both an active house of worship but also as an enduring symbol for the early religious freedom that the Rev. John Clarke negotiated with King Charles II of England in 1663. The Rhode Island Charter was a revolutionary document granting the freedom to practice their individual faiths and was to serve as “a Lively Experiment” to see if a community as diverse as Newport, Rhode Island would long survive. From the date of the charter to the adoption of that same religious freedom among all the original states with the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1788, it can be argued that Rhode Island in general, and Newport in specific, was among the places in the world that enjoyed the greatest religious freedom that existed at that point in time.

It is telling to remember that Quakers were being hanged in Boston in 1660 and that England and France had fought many long and bloody civil wars largely over religious differences between different Christian faiths in the period just before the Rhode Island Charter was adopted.

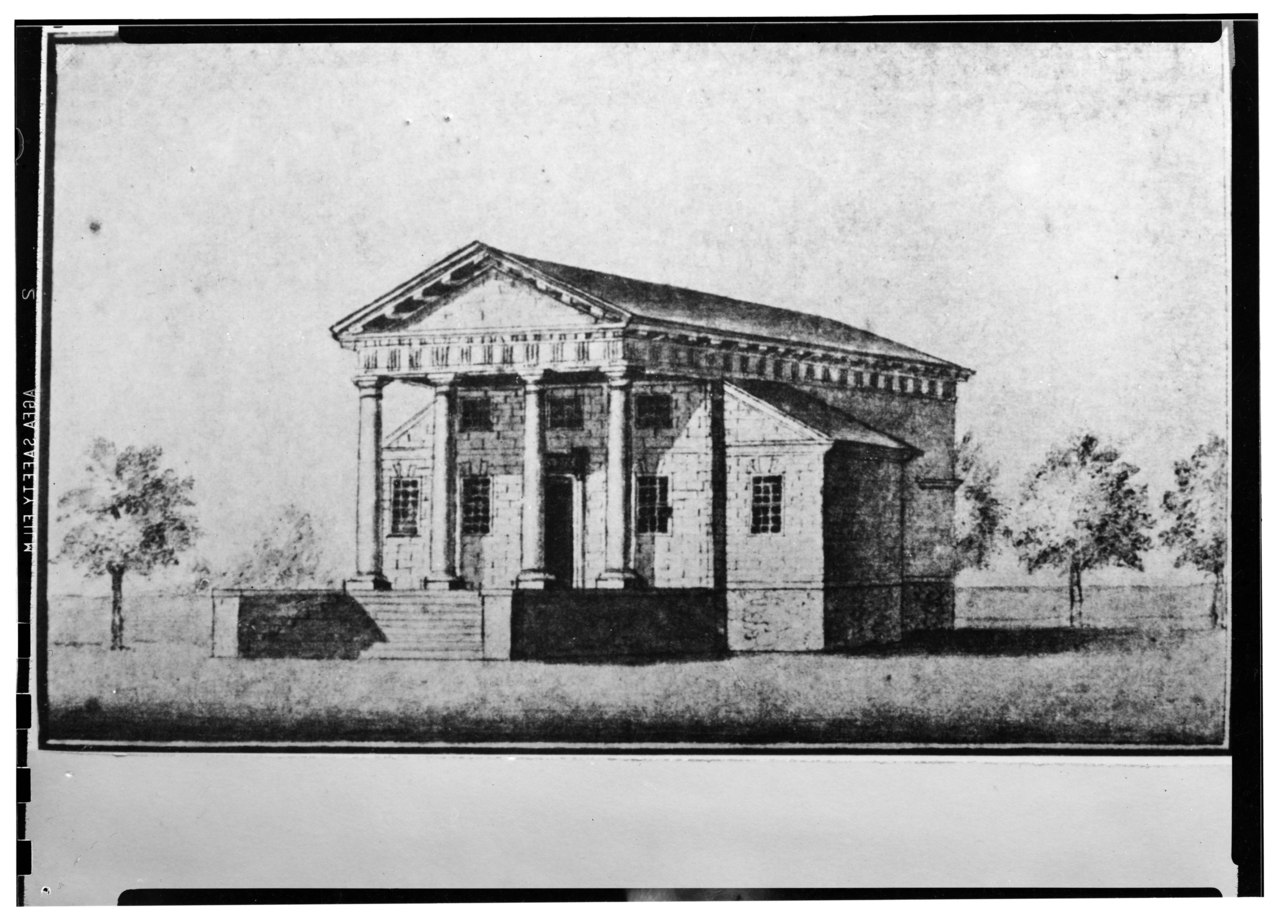

The Touro Synagogue structure was designed by Peter Harrison, one of the first architects to work on designs independent of the construction in the American Colonies. Harrison was also the designer of other important Colonial Era structures, including the Redwood Library (1739-’42) and the Brick Market (1761-’72).

It is believed that Harrison emigrated from England around 1740 at age 24, but returned for a time to be trained in architecture in one of the studios maintained by the English gentry. At that time in England, the “Neo-Palladian” style was sweeping away medieval styles, which had long dominated architectural design in Britain.

This new style was based on designs done nearly 200 years earlier by Venetian architect Andrea Palladio, who in turn was emulating the classical architectural forms of Rome and Greece of nearly 2,000 years previous to that.

Harrison is often credited as being the first American architect because he was perhaps the first to be taught architecture and to have his designs built by others. This was a large change from the design/builders such as Richard Munday or Asher Benjamin, who dominated church and public building construction during the better part of the 18th century.

Touro Synagogue is the only one of Harrison’s works that has been essentially unmodified by later additions or renovations. The exterior of the building is surprisingly austere, being a simple cube with a pyramidal roof. The only decorative features on the exterior are the dark sandstone band that belts the structure and the ornate neo-Palladian porch that hints at the far more elaborate and articulated interior hidden within.

The interior, through its magnificence, somehow gives the illusion of being larger than the simple box that contains it. As Ron Onorato observed in his AIA guide to Newport, the building is almost a metaphor for Jewish life in the 18th century; “richly lived on the inside, but modest and unpretentious on the exterior.”

Although there is a lack of primary resource materials, Harrison purportedly designed the synagogue without ever having seen one. As was often done in that era, he may have gone to his extensive library and found some designs of synagogues built in Holland and carefully studied those to use as models for the interior design. He certainly drew from books for his designs of the Redwood and Brick Market so the manner of his design is well established.

Each year, the congregation celebrates the open-mindedness that allowed Touro Synagogue to flourish in Newport with a reading of a letter proclaiming the ideals of religious tolerance that was written to the Newport congregation by George Washington at a time when the faith was often unwelcome elsewhere. The letter states “the Government of the United States gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.” These are sentiments that the world sorely needs more than two hundred and fifty years after the writing of that letter.

It is remarkable that not only was the Touro Synagogue built in a time when discrimination against Jewish people was rampant but that this beautiful building and congregation have survived, and even thrived, up to the present day in the face of many challenges and periods of religious persecution.

Externally, it is an expression of reserve and community mindedness. Internally it is a marvel of exuberance and celebration of the faith among those who had at long last found a place where they could practice their religion in freedom.

Ross Cann, RA, AIA, LEED AP, is an author, historian, and practicing architect living and working in Newport, RI. He holds degrees with honor in Architecture from Yale, Cambridge, and Columbia Universities.

Fascinating history of American “enduring symbol for the early religious freedom”!

Many thanks! It is our pleasure to share Newport’s rich architectural history with others.

Great article. Early Jewish inhabitants of Newport received religious toleration, but not full religious freedom and civic equality.